Paul Morphy: The Rise and Fall of a Chess Master

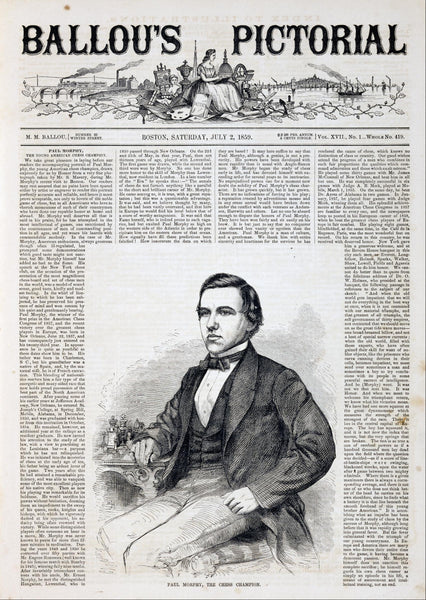

Paul Morphy vs. Löwenthal c. 1857, original photo by London Stereoscopic Company held at The Getty Museum

Just like Beth Harmon, Morphy began defeating older opponents at a young age. Born in 1837, Morphy gained attention at around the age of nine when he swiftly beat General Winfield Scott who had a reputation of being among the best of amateur players. By age twelve Morphy was playing the best contenders of New Orleans, including famed European player Eugène Rousseau. The publication of one of these games with Rousseau began Morphy’s rise to fame.

Morphy earned his law degree at the University of Louisiana (now Tulane University) but was not old enough to practice law, so he played chess in his free time. News of Morphy’s brilliance began to reach across the United States, and when the first national chess tournament was created, Morphy was persuaded into attending despite declining multiple times due to his father’s death a few months prior. During this First American Chess Congress, Morphy defeated every single challenger.

After winning the national tournament, Morphy immediately set his sights on Europe, not unlike Beth Harmon in The Queens Gambit. Morphy also began playing and winning blindfolded tournaments in which he often played eight opponents at one time while calling out his moves from across the room. Morphy became known as the world champion while he was still in his early twenties, yet never accepted the prize money for his victories.

But Morphy grew bored with the game, and his fame irked him. He stopped playing seriously in 1860 at only twenty-two years of age. The Civil War also caused him turmoil, as he felt conflicted over his loyalty to both the Union and Louisiana. After the war, Morphy attempted to practice law but had little success. He was renowned for his chess skills, not his law skills, and the public of New Orleans also questioned his dedication to the Confederacy, making him an unpopular choice for a lawyer.

Morphy’s law office also made him accessible to the public, and many wished to talk to him only about chess, which he deeply resented. The public criticized him for refusing money for the games he won. He grew withdrawn, angry, and suspicious, refusing to eat unless the food was prepared by his mother or sister. While in his forties, his family attempted to have him put in a Catholic institution for treatment, but he threatened to sue the nuns and they refused to take him. He became more delusional with time, asking people for loans and then refusing the money when it was offered. At the age of 47, he was found dead in his bathtub, having suffered a stroke.

Morphy’s madness has been a source of much consideration and theorizing. Since Morphy, other famous players have also become known for their troubled minds, causing an association between chess genius and madness. What toll does the mental strain of the game take on a player? Does a chess player require a certain propensity for madness and obsession to become a true master?

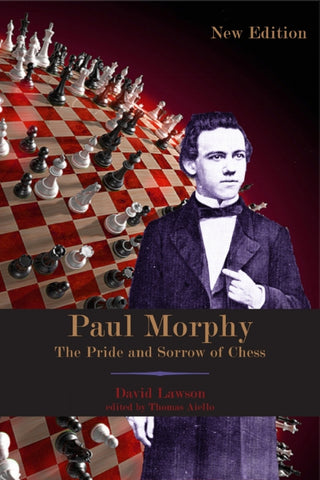

The Queen’s Gambit plays with this theme of chess madness as Harmon uses the game to cope with her life. You can read more about the parallels between Beth Harmon and Paul Morphy in this article by the New Yorker and learn more about Morphy’s genius and madness in Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess.